Surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa churned by small impacts

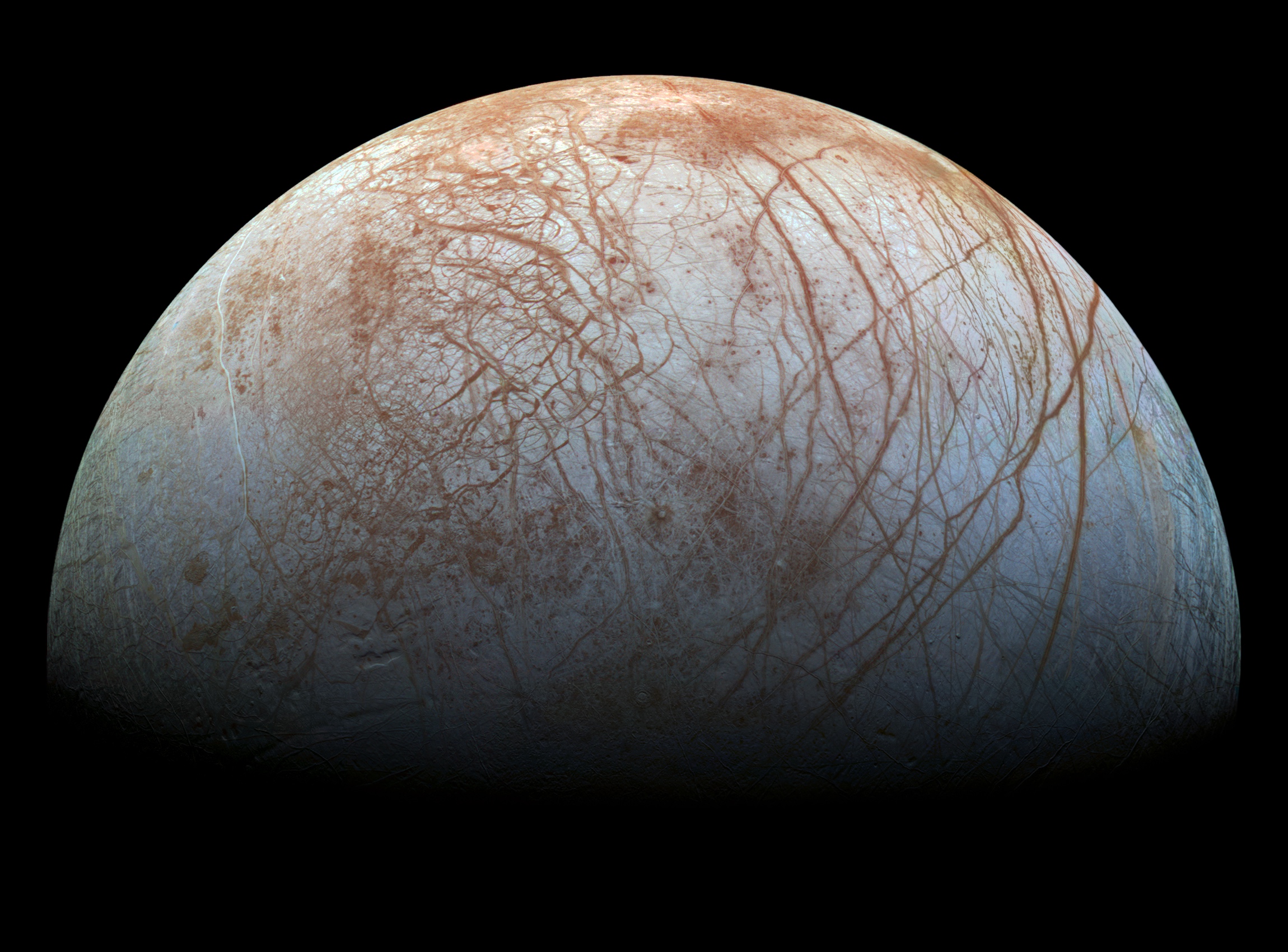

Surface of Jupiter's icy moon Europa made from images taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute

Surface of Jupiter's icy moon Europa made from images taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI InstituteJupiter’s icy moon Europa is of particular scientific interest because its salty ocean, which lies beneath a thick layer of ice, may currently have conditions suitable for existing life, and the ocean water may even make its way into the icy crust and onto the moon’s surface. New research and modeling, led by SOEST planetary sciences researcher Emily Costello, estimate how far down that surface is disturbed by the process called “impact gardening.”

The work, published July 12 in Nature Astronomy, estimates that the surface of Europa has been churned by small impacts to an average depth of about 12 inches (30 centimeters) over the last tens of millions of years.

It’s easy to see the impact of space debris on the Moon, where the ancient, battered surface is covered with craters and scars. Europa withstands a similar trouncing – along with a punch of super-intense radiation. As the uppermost surface of the icy moon churns, material brought to the surface is zapped by high-energy electron radiation accelerated by Jupiter.

And any molecules that could qualify as potential chemical biosignatures, which include chemical signs of life, could be affected at that depth. That’s because the impacts would churn some material to the surface, where radiation would likely break the bonds of any potential large, delicate molecules generated by biology; meanwhile, some material on the surface would be pushed downward, where it could mix into the subsurface.

“If we hope to find pristine, chemical biosignatures, we will have to look below the zone where impacts have been gardening,” said Costello, a postdoctoral researcher at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Geophysics and Planetology in SOEST. “Chemical biosignatures in areas shallower than that zone may have been exposed to destructive radiation.”

While impact gardening has long been understood as a likely process on Europa and other airless bodies in the solar system, the new modeling provides the most comprehensive picture yet of the process. In fact, it is the first to take into account secondary impacts caused by debris raining back down to Europa’s surface after being kicked up by an initial impact. The research makes the case that Europa’s mid- to high-latitudes would be less affected by the double-whammy of impact gardening and radiation.

“This work broadens our understanding of the fundamental processes on surfaces across the solar system,” said Cynthia Phillips, a Europa scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, and a co-author of the study. “If we want to understand the physical characteristics and how planets in general evolve, we need to understand the role impact gardening has in reshaping them.”

NASA-funded scientists are studying the cumulative effects of small impacts on Europa’s surface as they prepare to explore the distant moon with the Europa Clipper mission and study the possibilities for a future lander mission.

Managed by JPL for NASA, Europa Clipper will help develop that understanding. The spacecraft, targeting a 2024 launch, will conduct a series of close flybys of Europa as it orbits Jupiter. It will carry instruments to thoroughly survey the moon, as well as sample the dust and gases that are kicked up above the surface.

Content provided courtesy of JPL/NASA

Read also on KHON2, Voice of America, UH News, Maui Now, Big Island Now and Space.com.