Investigating water ice, space weathering on the Moon

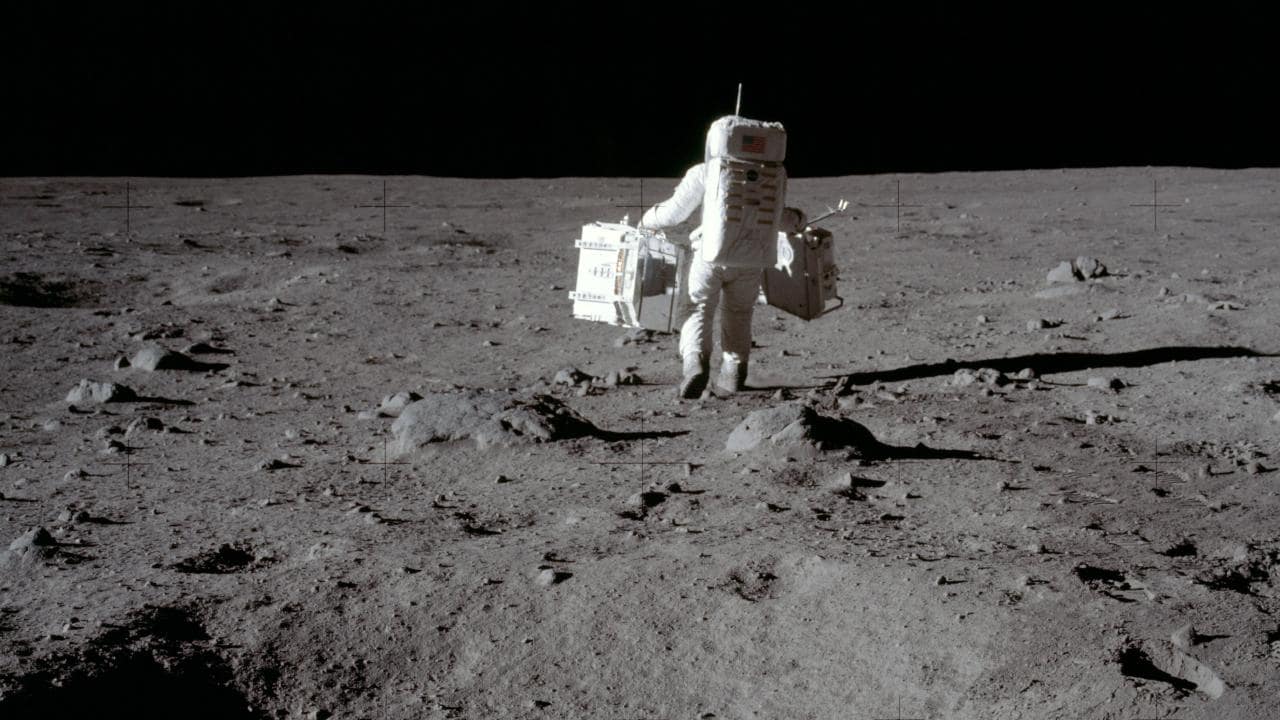

The first manned lunar landing mission, Apollo 11. Credit: NASA.

The first manned lunar landing mission, Apollo 11. Credit: NASA. When humans go back to the Moon — and NASA plans to return by 2024 — they’re going to need water. For now, the astronauts expect to bring their own. But future space explorers aim to take advantage of water recently discovered in little-explored regions of the Moon.

The water is stored as ice in shadowy parts at the Moon’s poles. A new consortium that includes researchers from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) will investigate the origins and evolution of water and other volatiles on the surface of the Moon. The team is one of NASA’s eight new Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institutes.

The UH component of the grant will bring $2.7 million to the university over five years and will be led by Hope Ishii, research professor at SOEST’s Hawai‘i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP). Other members of the UH team are Paul Lucey, John Bradley, Shuai Li, Tayro Acosta-Maeda, and Barbara Bruno at UH Mānoa and Heather Kaluna at UH Hilo, and several graduate students and postdoctoral researchers will be engaged in the effort.

The grant to the Interdisciplinary Consortium for Evaluating Volatile Origins (ICE Five-O) will allow the researchers to study the effects of interactions of lunar soil and simulants with volatiles at nanometer length scales in the transmission electron microscope housed in UH’s Advanced Electron Microscopy Center – all while controlling the temperature from the cryogenic conditions in permanently-shadowed regions to the warmer temperatures of sunlit regions.

This will also allow the researchers to study the effects of space weathering in the harsh space environment. Ions streaming from the sun and high-velocity dust-sized particles release huge amounts of energy that transform lunar minerals into glass and can destroy ices, or lead to a variety of chemical processes — for example, transforming molecules of water (H2O) ice and carbon dioxide (CO2) ice to methane ice (CH4).

“Studying the effects of volatiles and space weathering on the minerals, glasses, and organics in the Moon’s soil will ultimately contribute to our ability to trace volatiles backwards to their sources,” said Ishii.

“Revealing the source of the Moon’s water can, in turn, inform us about how the Earth got its water,” said Jeffrey Gillis-Davis, research associate professor of physics at the Washington University – St. Louis and the principal investigator of the ICE Five-O team. “If we see that the water wasn’t sourced entirely from lunar volcanoes — that it was delivered later — then it would be a strong indicator that Earth’s oceans formed at least in part by water delivered after Earth’s formation, rather than during its accretion in the early solar system.”

The UH team will also perform remote sensing campaigns, led by HIGP research professor Paul Lucey, to detect organics and better quantify the water abundance on the lunar surface.

The public outreach component of the ICE Five-O project, led by HIGP research specialist Barbara Bruno, will follow the recommendations of the Kulana Noi‘i, a resource developed by Hawai‘i Sea Grant that provides guidance for building and sustaining long-term relationships between communities and researchers. The outreach team will invite community members to join in the development of educational programing that utilizes existing NASA educational resources and Hawaiian indigenous knowledge.

The research led by the ICE Five-O team will help guide critical parts of the planning for future manned missions to the Moon and share this exciting field of science with the public.

Portions of this content provided by Washington University – St. Louis.

Read more on UH News and The Source.