How we’re teaching endangered coral reefs to help themselves

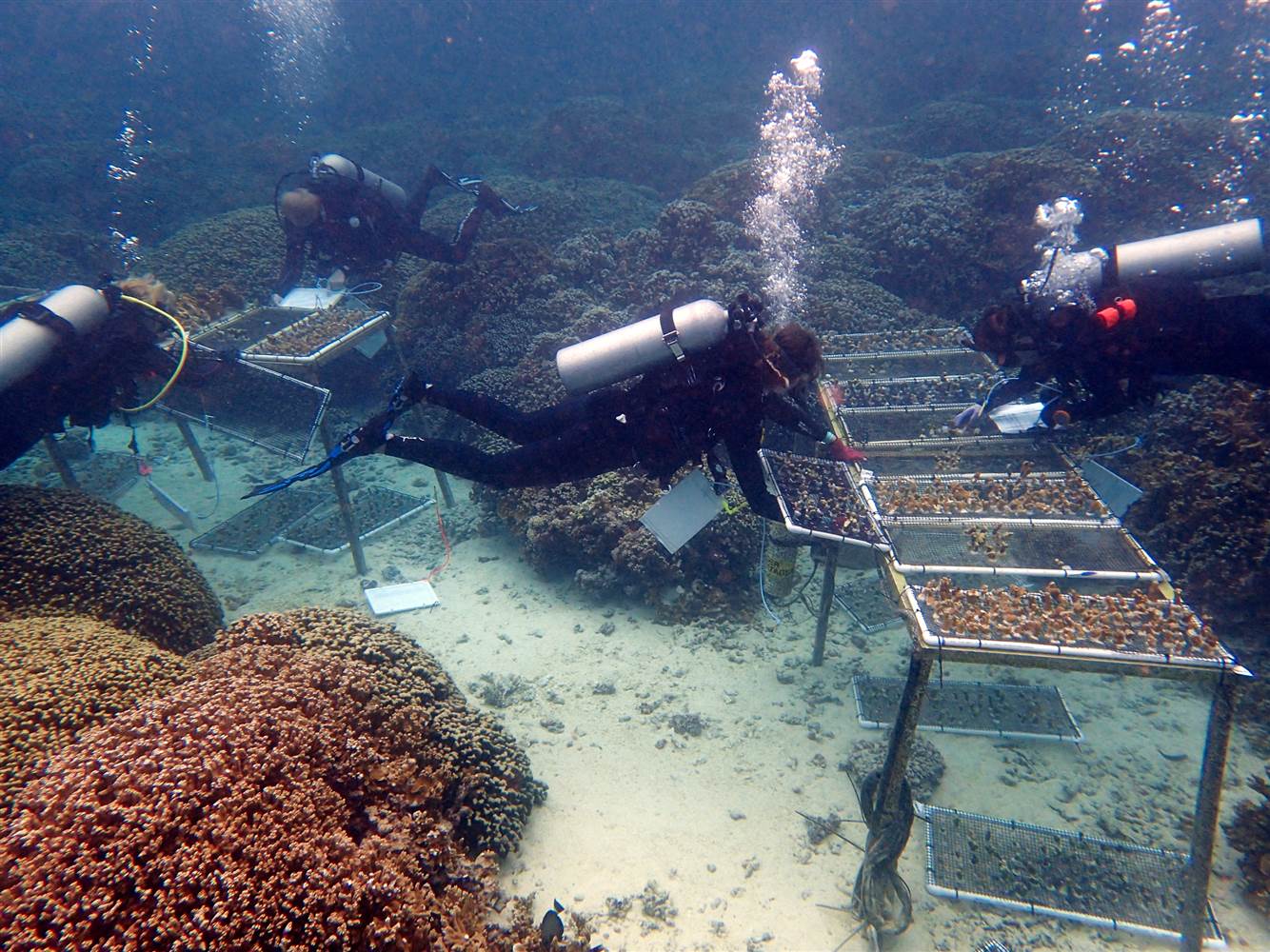

Divers from Ruth Gates' lab check on corals for a transplant experiment. The team moved thousands of coral fragments between two sites to see how differences in water acidity affected them. Image courtesy of Shayle Matsuda.

Divers from Ruth Gates' lab check on corals for a transplant experiment. The team moved thousands of coral fragments between two sites to see how differences in water acidity affected them. Image courtesy of Shayle Matsuda.Around the world, coral is under siege. Battered by a changing climate, destructive fishing, and other threats, reefs are disappearing. Just last year, the Great Barrier Reef suffered the worst die-off ever recorded. If nothing is done, nearly all reefs will be in serious danger by 2050. Many people depend on reefs for their food and livelihood. They’re home to more than 25 percent of marine creatures, supplying us with fish and sources of new medicines to fight cancer and other diseases. Reefs also form natural seawalls that protect shorelines from storms and waves, and are magnets for tourism.

To save the world’s reefs, researchers are transplanting healthy coral into damaged landscapes, and pioneering new strategies to breed stronger corals and guide infant corals to settle on and rebuild degraded reefs. Planting new corals by hand is labor-intensive and won’t be enough to replenish the world’s reefs. But scientists are coming up with plenty of new strategies, too.

“No two reefs in the world are the same,” say Ruth Gates, director of the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB). “What we do in Hawaii may not work as well in Australia.”

Gates wants to tweak corals so they will be better suited for future oceans. She’s investigating why some corals tolerate heat and different strains better than others. “I decided that rather than documenting the death of coral reefs that I’m going to focus on survivors,” she says. Her team is identifying which corals on a reef persevere while their neighbors succumb to bleaching, then breeding the strongest of them. This year, they will give the offspring of these unions a “stress test” to find out if they have an edge at coping with difficult conditions.

Read more about it at NBC News.