Coral toolkit allows floating larvae to transform into reef skeletons

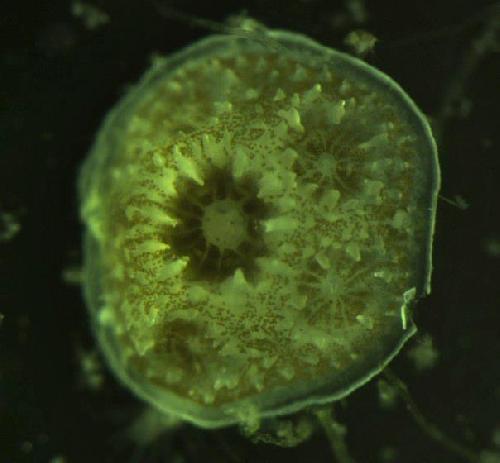

A juvenile lace coral (Pocillopora damicornis), with coral tissue and algal symbionts (brown dots within the tissue) covering the newly grown skeleton. Image courtesy of Hollie Putnam.

A juvenile lace coral (Pocillopora damicornis), with coral tissue and algal symbionts (brown dots within the tissue) covering the newly grown skeleton. Image courtesy of Hollie Putnam.In a study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers from UH Mānoa, Rutgers University, and the University of Haifa identified key and novel components of the molecular “toolkit” that allow corals to build their skeletons (called biomineralization) and described when—in the transformation from floating larvae to coral skeleton—these components are used.

Corals are the sum of a symbiotic relationship between cnidarian animals and millions of single-celled algae that live inside their tissues. These symbiotic algae photosynthesize and provide the energy corals need to build their skeletons. In turn, the skeletons form the structure and framework of coral reefs that provide habitat to fishes and other animals. Coral reef are so large they can be seen from space, and generate goods and services valued on the order of billions of dollars annually.

“Our research on reproduction in the lace coral, Pocillopora damicornis, provided the perfect opportunity to look at a natural on-off switch in coral biomineralization,” said co-lead author,” Hollie Putnam, Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) assistant researcher. Corals release their offspring as swimming larvae with no skeleton. The larvae change shape, settle onto the reef, and start to build their skeletons. Putnam and Ruth Gates, senior researcher and director of HIMB, collaborated with scientists from Rutgers University, and the University of Haifa to examine gene expression and the production of proteins at these different life stages.

Read more about it in the UH System News and at Science Codex.