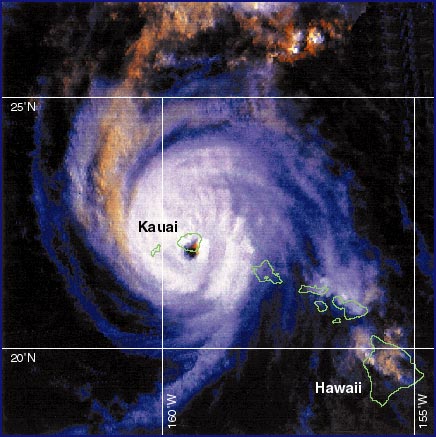

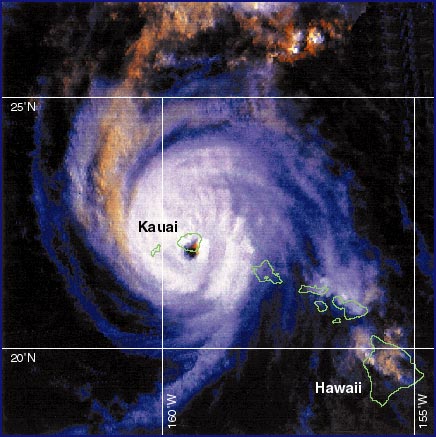

Figure 1: High resolution infrared image of Hurricane Iniki making landfall on Kauai at 3:15 PM HST on 11 September 1992. The image was taken by a NOAA polar orbiting satellite ~500 mile above the Earth.

(Click on image to see full size)

HURRICANES form in areas of enhanced thunderstorms over warm, tropical oceans and are the most destructive storms on Earth (Figure 1). The destructive fury of hurricanes comes from a combination of high winds, heavy rains, and abnormally high waves and storm tides. The deadliest hurricane in U.S. history occurred in Galveston, Texas in 1900 when an estimated 6000 people perished. One of the costliest natural disasters ever to hit the U.S. was Hurricane Andrew, which resulted in more than $30 billion in losses and 53 related deaths. In the western North Pacific, the storms that annually threaten the Philippines and Japan are called typhoons. Over the Indian Ocean the same type of storm is called a cyclone. In 1970 more than 300,000 people lost their lives in a storm surge and tide that struck Bangladesh. A storm surge is a rise in the level of the sea caused by effects of wind and low atmospheric pressure on the ocean.

Figure 1: High resolution infrared image of Hurricane

Iniki making landfall on Kauai at 3:15 PM HST on 11 September 1992. The

image was taken by a NOAA polar orbiting satellite ~500 mile above the

Earth.

(Click on image to see full size)

Hurricanes in Hawaii: Hurricanes are relatively rare events in the Hawaiian Islands. Records show that strong wind storms have struck all major islands in the Hawaiian Island chain since the beginning of history. The first officially recognized hurricane in Hawaiian waters was Hurricane Hiki in August of 1950. The identification of tropical cyclones improved with increased commerce and aircraft activity following WWII and improved dramatically with the launch of the TIROS 1 weather satellite in April of 1960 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: All tropical cyclone tracks passing within

~200 miles of the coast of the Islands of Hawaii during the period 1949

to 1997. Prior to 1950, a general lack of wind data has resulted in a sketchy

record. From 1832 to 1949 only 19 tropical cyclones were identified from

scattered written records and ship reports.

(Click on image to see full size)

Since 1950 five hurricanes or tropical storms have caused serious damage in Hawaii. Hurricane Nina (1957) produced record winds in Honolulu. Hurricane Dot (1959) caused damage to Kauai. Hurricane Estelle (1986) produced very high surf on Hawaii and Maui and floods on Oahu. Kauai also received the brunt of Hurricane Iwa, which struck on 23 November 1982 and produced an estimated $234 million in damage.

The destructive force of hurricanes in Hawaii was powerfully demonstrated on 11 September 1992 when Hurricane Iniki struck the island of Kauai with sustained winds of 130 mph and caused over $2.3 billion in property damage (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Sheets of roofing iron, a pallet, broken plants

and other debris fly through the air at the height of Hurricane Iniki in

Lihue, Kauai (Photo by Bruce Asato, courtesy of the Honolulu Advertiser).

(Click on image to see full size)

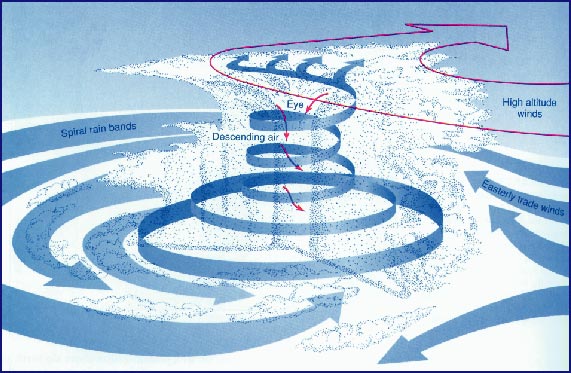

Anatomy of a Hurricane: The core of a hurricane is characterized by a small central region known as the eye, within which the winds are light and there are few clouds. Winds increase rapidly as one moves out of the eye and into a surrounding ring of thunderstorms referred to as the eye wall (Figure 4). The winds in a hurricane are a maximum near the surface and decrease with height. In the Northern Hemisphere, a hurricane's circulation includes low pressure and counter-clockwise inflow at the surface, and high pressure and clockwise outflow at upper levels (Figure 5). The overall diameter of the hurricane circulation is typically between 300 and 600 miles.

Figure 4: Schematic showing path and destructive elements

of Hurricane Iniki across Kauai. Hurricanes impact Hawaii through the combined

effects of strong winds, possible tornadoes, torrential rains, and elevated

tides and large waves on coastal and inland areas. These destructive forces

are magnified on the right side of the eye wall when facing in the direction

in which the hurricane is moving.

(Click on image to see full size)

Figure 5: Conceptual diagram showing the internal structure

and circulation of a mature hurricane. (From NOAA, Hurricane, Washington,

DC: Superintendent of Documents, 1977) Given a source of moisture from

a warm ocean surface and a lack of destructive wind shear, hurricanes typically

last for a week to 10 days.

(Click on image to see full size)

Hurricane Formation: The necessary conditions for one of the numerous convective disturbances over the tropical oceans to intensify into a hurricane are related to the wind field's ability to produce and concentrate warm air. Warm air is less dense than cold air leading to low surface pressure. As the wind strength increases over a warm ocean surface, the flux of heat and moisture also increases and a cycle of intensification results. Only one in ten tropical disturbances (winds up to 38 mph) develops into a tropical storm (winds 39 to 74 mph), but fully seven in ten tropical storms do develop into hurricanes (winds >74 mph). Together these storms are referred to as tropical cyclones.

There are five prerequisites for hurricane formation that are related to the formation of the warm core in the hurricane. (1) Warm ocean water with temperature more than 80°F (26°C) to a depth of ~100 feet (50 m), so that cooler water cannot easily be mixed to the surface by winds. (2) Unstable atmosphere characterized by enhanced thunderstorm activity. Latent heat is released efficiently in the updrafts of deep clouds. (3) High relative humidity in the middle troposphere; moist air weighs less than dry air, making it buoyant and contributing to lower surface pressure. (4) A pre-existing disturbance with cyclonic circulation; as the air in the disturbance converges, angular momentum is conserved and the wind speed increases. (5) Small wind shear or little change in the wind speed or direction with height in the vicinity of the developing storm so that warm air is concentrated over one area and not blown apart by the winds. When a hurricane moves over land or cold water, the supply of energy is reduced, and the wind speeds diminish. Over land, frictional forces also act to weaken the storm.

Figure

6: Tracks of all Central Pacific hurricanes from 1949 to 1997. Track segments

for hurricanes of category 3 are shown in red. August mean positions of

areas of warm (>83°F) and cool ocean water (80°F is minimum SST

for hurricane formation) are indicated by shading. August mean wind conditions

at the surface are indicated by arrows and the 1016 mb contour of constant

sea-level pressure (isobar). August mean wind conditions aloft are indicated

by the 200 mb ridge line that separates easterly from westerly flow aloft

(arrows). Most of these storms (~70%) form over the eastern Pacific and

pass into the central Pacific from the east. The mean storm track follows

parallel to the summer mean sea-level pressure contours (isobar) and stays

over warm water.

Figure

6: Tracks of all Central Pacific hurricanes from 1949 to 1997. Track segments

for hurricanes of category 3 are shown in red. August mean positions of

areas of warm (>83°F) and cool ocean water (80°F is minimum SST

for hurricane formation) are indicated by shading. August mean wind conditions

at the surface are indicated by arrows and the 1016 mb contour of constant

sea-level pressure (isobar). August mean wind conditions aloft are indicated

by the 200 mb ridge line that separates easterly from westerly flow aloft

(arrows). Most of these storms (~70%) form over the eastern Pacific and

pass into the central Pacific from the east. The mean storm track follows

parallel to the summer mean sea-level pressure contours (isobar) and stays

over warm water.

(Click on image to see full size)

The climatology of hurricane tracks over the central Pacific shows a mean track passing to the south of the Hawaiian Islands (Figure 6) and a maximum hurricane occurrence during the late summer when the ocean surface is warmest (Figure 7). Storms that approach the Hawaiian Islands from due east have historically weakened east of Hawaii under the combined influence of unfavorable westerly wind conditions aloft, resulting in large wind shear and cooler sea-surface temperatures. However, natural variability in the circulation of the ocean and atmosphere has allowed potentially destructive depressions and tropical storms to reach Hawaii from the east since 1950 (Figure 2), and there is historical evidence of one early hurricane (1871) that approached from the east and impacted the islands of Hawaii and Maui. Hurricanes Dot, Iwa, and Iniki all approached from the south and passed near Kauai. This unusual track requires a breakdown of the semi-permanent ridge of high pressure to the north of the islands, which occurs when a trough of low pressure in the midlatitude westerlies approaches the island chain from the northwest. Such troughs are generally confined to higher latitudes, except in winter.

Figure 7: Monthly climatology of hurricane occurrence

in the Central Pacific. The peak in hurricane activity is in late summer

when ocean temperatures are warmest.

(Click on the image to see full size)

Figure 8 Destruction in the wake of Hurricane Iniki.

(Photo by Charles Fletcher).

(Click on the image to see full size)

Hurricane Impact in Hawaii: The potential for property damage in Hawaii is increased because of the numerous lightly constructed buildings and dwellings (Figure 8). Flying debris from these structures and airborne vegetation increase the potential for serious damage to neighboring properties and utility lines (Figure 3). Hawaii's topography funnels and amplifies the tropical cyclone winds across ridges and through island channels. The terrain in Hawaii also focuses torrential rains on mountain slopes, resulting in destructive flash floods and landslides. For these reasons, even a relatively weak tropical storm can potentially result in considerable property damage and losses if it makes a direct hit on populated Oahu.

In Iniki and Iwa, the storm surge and wave action had a dramatic impact on the south shore of Kauai, resulting in a total loss of numerous coastal properties and significant damage to waterfront roads and other coastal infrastructure (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Large wave generated by Hurricane Fernanda impacting

Koko Head, Oahu, September 1993 (Photo by Steven Businger). Fernanda caused

major erosion on Oahu.

(Click on image to see full size)

Hurricane Hazard Mitigation: When a hurricane is approaching a coastal location, early evacuation to higher ground of those people susceptible to the destructive force of the storm surge is essential. The National Weather Service provides important guidance to emergency managers by issuing hurricane advisories. Generally, the National Weather Service issues a hurricane watch when there is a possibility of landfall within 36 hours. A hurricane warning is issued when landfall is likely within 12 to 24 hours. For information regarding how to prepare for the hurricane season and how to respond to warnings of an approaching storm please contact the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC), 2525 Correa Road, Suite 250, Honolulu, HI 96822, (808) 973-5270, www.nws.noaa.gov/pr/hnl/. For access to related NOAA publications and brochures go to www.nws.noaa.gov/om/. Up-to-date weather information for the Pacific is available at the UH Meteorology Department homepage at lumahai.soest.hawaii.edu.

Homeowners in Hawaii can help themselves by making their homes and buildings less susceptible to damage by hurricanes and windstorms. Information on how this can be done appears in a brochure entitled "Hurricanes in Hawaii: What are the Risks of Damage? What can Home Owners do to Reduce their Risks?" available from the Hurricane Relief Fund, P.O. Box 541, Honolulu, Hawaii 96809, telephone (808) 586-3100.

This poster was developed for the Hurricanes and Extreme Weather

Phenomena Symposium presented by the Center for the Study of Active Volcanoes

and sponsored by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under cooperative agreement NA67RJ0154,

and the COMET program (UCAR S98-87020).

Web layout by Ray Tanabe - 25 September 1998